x Sally Burch: "Social" networks encourage the creation of false news through their algorithms and then ask for restrictive laws to fight them

As the use of digital social networks (RSD) is representing a growing space in the communication scene, from the media to the advertising, going through the interpersonal, it is increasingly complex to appreciate its scope and impact on how we inform ourselves, from what sources, in what ways we communicate and share content, and with whom.

One of the central elements that affects how these changes occur is the dominant private corporate model in digital platforms. That model of Internet development and digital technologies was not the only one possible. On the one hand, there were large public investments to develop the technology, which was then handed over to the private sector for usufruct. On the other hand, online exchange interfaces were born much earlier than social networking platforms and were part of the Internet from the beginning, usually in spaces created and self-managed by users, such as, for example, electronic thematic lists. , murals ("bulletin boards"), newsgroups, or open access databases.

The entry on the scene, towards the beginning of this century, of the so-called [better said self-proclaimed] Web 2.0 - whose promotional discourse speaks of "radical decentralization, radical confidence, participation ... user experience, control of the information of each one ..." - It coincides with the large capital investments in the new technology companies in Silicon Valley and - after the bursting of the stock market bubble of the "dot.com" - the need to look for ways to make them profitable, which did not seem so easy in an area where the contents are freely shared.

With digital social networks, which had begun to appear in the last decade of the last century, companies find a solution: create platforms where people interconnect, share content and generate data, from which they create profiles of each user that , in turn, are sold to advertisers. The logic that is imposed implies that the more users use the platform, the more data they accumulate, the more sales are generated. For this reason, fenced spaces are created so that users do not leave the platform but perform most of their online activities within it. Therefore, in many business social networks, you can only exchange with those who have an account on the same network, a fact that goes against the spirit with which the Internet was born, as a protocol that allows intercommunication between all platforms.

These practices lend themselves to the formation of "natural monopolies" due to the "network effect": that is, users opt for the most popular digital networks, where their friendships, clients, and topics of interest are. These are today called youtube, facebook, twitter, instagram ... whose power is such that they are eliminating or absorbing the competition.

The algorithm trap

From the logic of profitability, what users do in the platform matters little, with that they continue to feed with their data, generating traffic and consuming advertising. Under the pretext of improving the experience for their users, companies develop algorithms (that is, sets of computational rules that allow carrying out a series of operations) whose functions include determining what will be visible -or not- for each user, supposedly depending on their identified interests [through the searches they perform or the advertisements they visit], but often incorporating other criteria aimed at selling more publicity or even motivating levels of addiction to the constant use of the network and compulsive behaviors.

It has been found, for example, that negative emotions lead to stronger online action tendencies than positive emotions; therefore, certain algorithms end up prioritizing those contents that provoke reactions of anger or hatred in the user. Also, when a user shows interest in content with extremist politico-social positions, the algorithm offers new even more extreme content [as long as they are from the right, for example against foreigners]. With this, these systems contribute to radicalize positions and sharpen existing antagonisms in society, to the point that, in contexts of strong conflict, they have come to catalyze collective actions (offline) of physical violence and even cases of lynching. As a consequence, the space for political debate and the confrontation of ideas, programs, thesis and the search for minimum consensus between divergent points of view are narrowed.

To this is added the constant harassment to the user so that he does not disconnect, that he continues to consume content and to feed his profile. Snapchat, for example, one of the networks preferred by youth, where photos last a limited time, encourages the user to be permanently connected: that is not going to miss something that friends have posted or have seen. It even has a scoring system that penalizes who gets disconnected. This tends to generate levels of addiction and dependence.

Little aware of the power of these algorithms, we generally use the RSD platforms uncritically, trusting companies that do not render accounts to anyone, letting them influence, with opaque algorithms, the relationships we form, the information we consume, the audiences we reach, who knows about our private life, and even who we vote for.

Does the current RSD model run out?

The recent scandals about the proliferation of false news, the lack of ethics and transparency, the abuse of personal data and the interference in electoral processes have begun, however, to undermine this confidence.

The increasingly frequent scandals around the abuses of certain platforms, particularly exploiting personal data, have been one of the catalysts that have ended up generating a negative reaction. The public user begins to feel used, his privacy is violated, he realizes that he does not control what content he can see or who sees the content he posts, or he feels tired of advertising. As a result, more and more users decide to close their accounts in certain RSDs or migrate to another platform that seems to offer better guarantees. Facebook has been one of the most affected networks by such scandals.

A recent study records for the first time a decrease in the number of users in some RSD (twitter and snapchat), in the second quarter of this year, and almost static growth in others (like facebook, which lost, in addition, a million users in Europe) [1]. This evidences, perhaps, the ephemeral that can be a platform or another, but not the system itself, since they are the same transnational companies that are creating the alternative platforms to which most users migrate. Young people, in particular, are migrating preferably to graphic platforms such as instagram (facebook) or youtube (google); and many users prefer to use messaging platforms with encryption to share information, such as whatsapp (facebook).

However, in the case, for example, of messaging systems such as whatsapp, it has cost companies to find a model that allows their use to be monetized in the same way as RSDs, since they respond to other logics. In fact Facebook recently announced that from 2019, will introduce whatsapp advertising; this could compromise the privacy of communications, since it has been revealed that the company plans to extract key words from the messages (supposedly encrypted) to guide advertising. It remains to be seen how many users end up migrating from whatsapp to some other messaging system. It is also worth noting that with respect to the use of social networks in politics, migration to messaging implies that the use and impact of these systems can not be publicly evaluated to spread false news or hate messages, since they are private messages. [Although in the case of the Bolsonaro fascist triumph in Brazil, it was possible to know, since massive deliveries were made to millions of telephone numbers by means of robots, so that even people on the left received them].

Then, in the background, the question arises whether the solution is to move each time from a commercial platform to avoid the inconveniences, or if it is rather the current commercial model itself that poses a serious problem, not only in individual terms, but for society itself.

In this context, free social networks present an interesting alternative, especially to protect the private and dynamic internal interactions of organizations or communities, where maintaining control and guaranteeing privacy is key; but also, increasingly, they are becoming spaces for alternative public dissemination.

A space of political dispute

In any case, in the current reality, those who act in the media, political, social or cultural areas can hardly ignore the most popular commercial RSDs. Like it or not, they occupy a more and more central place in public life and as such constitute a space of dispute to interact with broad audiences.

In fact, numerous social actors, organized sectors, alternative media or artists have turned commercial RSD into spaces that promote organization and resistance. By appropriating these channels of dissemination and exchange, they have been able to call mobilizations with a much greater scope than with previous methods, share creativity, opinions and versions of reality excluded from the hegemonic media, amplify them through viral processes, or generate new cultural expressions. Technopolitics and technoculture are already part of the new reality, particularly among youth, and exceed the parameters set by the owners of the platforms, generating innovative organizational and communication forms that flow between the online and offline worlds.

In any case, to have an effective participation in this dispute it is important to understand that it is a minefield, planted with opaque algorithms that respond to particular interests [capitalist], so it is necessary to act with caution and with an understanding of the logic that there they operate. Among them, we can mention the ease with which rumors and false news are distributed, and the difficulty of identifying their sources [the clearest example is in the alleged repression of the right-wing groups in Venezuela]; the limitation that implies reducing thought and complex ideas to the size of a 280-character tweet; and also the tendency of algorithms to exacerbate the polarization of opinions, by giving users more than they "like". It is also important to understand that the power sectors already have a developed arsenal, with heavy investments, to prevail in this dispute.

Precisely, a recent study by the University of Oxford [2], evidences evidence of formally organized manipulation of social networks in 48 countries on all continents, (20 more than the previous year), mainly in the form of campaigns misinformation in pre-election periods [a good example is the campaign against AMLO in Mexico]. This manipulation is practiced mainly by government agencies or political parties, and aims, among other things, to create and amplify hate speech or personal or group defamation; generate false narratives and information; divert thematic attention; collect data illegally; or undermine democratic processes, censoring counter-narratives. There are also numerous consulting firms specializing in these practices [such as Cambridge Analytica, to which facebook delivered the data of 87 million users to interfere in the US elections, it is not yet clear whether for or against Trump].

The recent elections in Brazil show, again, the seriousness of this manipulation for the future of our democracies. It has been denounced that the electoral campaign of Jair Bolsonaro has contracted telephone lines in the outside of the country to send messages that are spread through a myriad of whatsapp groups, reaching tens of millions of Brazilians with lies and hate messages against the PT, that have permeated popular consciousness [3].

So, it is a serious challenge for sociopolitical actors who fight for democracy and social justice to think about how to face and counteract these manipulations, avoiding falling into the same questionable procedures.

Should we legislate on RSD?

Given the evidence that has come to light about the scope of such practices, particularly in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica / facebook scandal and its interference in US elections with illegitimately obtained data [without users' consent], the lawmakers of that and other countries have begun to recognize the need to regulate the practice of digital platforms. The problem is that the proposals they raise could sometimes be worse than the problem itself.

One thing is the need to regulate what companies can and should not do with personal data and in which cases the authorization of the person concerned is required. Another thing is to regulate what individuals can or can not do on the Internet, beyond what is already stipulated in national laws and international norms related to human rights and freedom of expression.

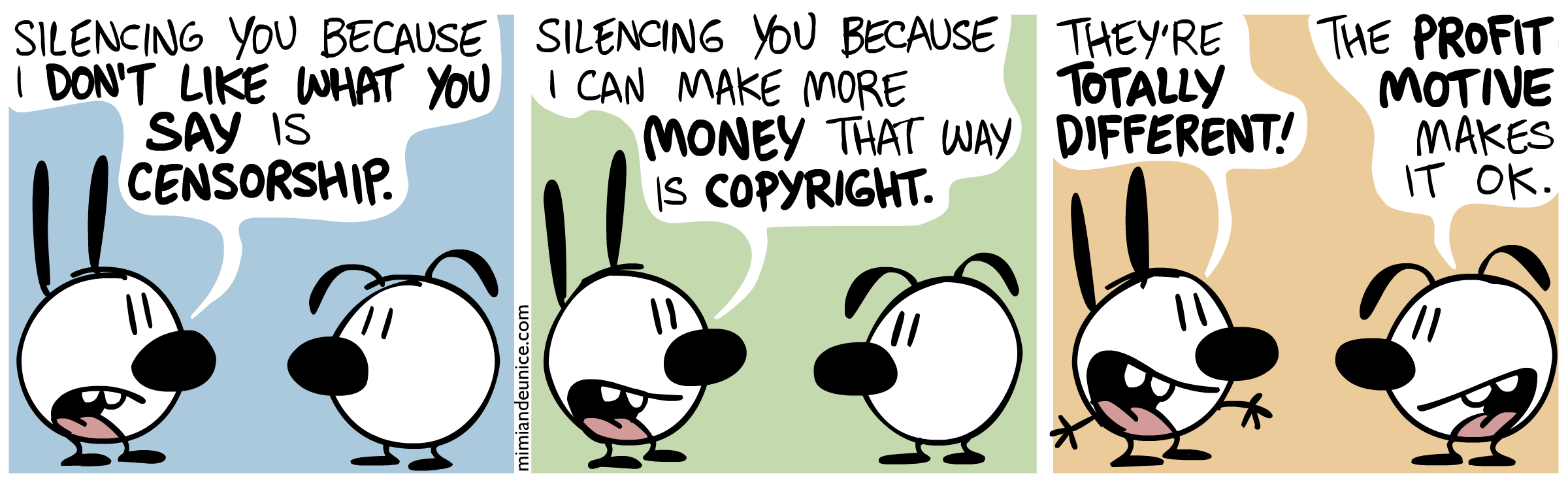

Also, they worry about the (false) solutions that the same companies are proposing to combat the fake news, when the power to censor messages and sources according to their own criteria is arbitrarily granted; or agree on agreements with supposed "news check agencies" to review the "veracity" of the news in the RSD, (being that in several cases these agencies are the same large media that have shown themselves unethical in terms of false news ). There are even countries where it is proposed to commission, by law, this role of judging content to the police.

Easily [or fatally] such mechanisms will become new ways of silencing dissenting voices. Therefore, it is urgent to open a broad public debate on the meaning of possible regulations, maintaining as a central principle the defense of freedom of expression as a right of citizenship, not as a right of a few large media or granting media companies or technological the role of judges or censors.

Full text at: https://www.lahaine.org/bF4I

No comments:

Post a Comment